Shown in photo (L to R) Randolph A. Hearst, Gary Hoachlander (MD-1966), Rosalie Wynn Hearst, Alice Mae Nicholson (MD-1966) and George Hearst

One of the milestones of the United States Senate Youth Program’s Washington Week is composing a reflection essay once delegates have boarded planes and trains and returned to hometowns across the United States. Each year essays arrive filled with inspiration, poignancy and revelation. Reading them, the emotions are so vivid that the week feels like it ended only hours ago. Evidently, these memories do not fade with time. The USSYP caught up with Gary Hoachlander, a delegate from Maryland in 1966. Mr. Hoachlander exemplifies one of the pillars of the program: public service; with a long career in academia, the federal government and the nonprofit arena. He is currently president of ConnectED: The National Center for College and Career, based in Berkeley, California.

Gary Hoachlander brings Washington Week 1966 to life in this essay of reflection written just weeks ago:

We arrived at the Mayflower Hotel on Saturday, January 22, 1966. Randolph A. Hearst, Mrs. George Hearst, and George Hearst warmly welcomed me and my co-delegate from Maryland, Alice Nicholson. They individually greeted each of the 51 delegations (every state plus the District of Columbia). It was such a wonderfully kind and personalized beginning to our week.

In the days that followed, we had the opportunity to meet, talk, and interact with so many of the nation’s top leaders. We participated in a mock session of Congress, where we heard from Speaker of the House, John McCormack (D-MA-9th). During this session, Representative Charles Weltner (D-GA-5th) urged that 18-year-olds be given the right to vote. Surprisingly, after the speech, an informal survey of 25 of the Senate Youth delegates found that only two supported the proposal and two were undecided. I’m not sure whether I was part of that survey or, if so, what my position was. One of the more vocal delegates opposing the proposal was Dale Allen from Ft. Lauderdale, Florida saying, “At 18, kids are just getting out of high school—they’re not ready to accept responsibilities.” I did not know Dale then and don’t think we met during that week (in that world long before social media, none of the delegates were likely to arrive knowing or having corresponded with each other). However, three years later, during my junior year at Princeton University, he would become one of my college roommates. I suspect by then Dale, and if I also earlier shared his view, me as well, had changed our opinions. In any event, five years later on July 1, 1971, the nation ratified the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution giving citizens over age 18 the right to vote. It was the quickest ratification of an amendment in history.

We visited the Supreme Court, and Alice and I had the privilege of speaking with Associate Justice Tom Clark. He shared with all of us how the justices hear and decide cases. We walked the halls of the Capitol and heard from Senate Majority Whip Russell Long (D-LA), Senate Minority Whip Thomas Kuchel (R-CA), and Senator John Tower (R-TX), a powerful member of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

On the Tuesday of Washington Week, at a luncheon in honor of the Senate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey (who then served as the Honorary Chair of the Senate Youth Program’s Advisory Committee) spoke to us about the need for all people to “learn to live and work together or they will perish together.” As we confront the Covid-19 crisis, that message is as relevant today as it was more than 50 years ago. At the luncheon, we were seated alphabetically by state. On my left sat Maryland Senator Daniel Brewster, with whom I would have the opportunity to ‘job shadow’ later in the week. As Massachusetts follows Maryland in the order of the states, on my right was U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who had joined his younger brother, Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA). A little more than two years later, I would watch Robert Kennedy’s assassination on television and recall in tears his encouraging me to enter a life of public service.

Later that evening, we heard from Senator Ted Kennedy, who had just returned from a trip to Vietnam. Few if any of the delegates, certainly not I, had yet begun to appreciate the seriousness of the war and its impact on our generation and the nation at large. He predicted an “enduring, long and costly war” and advocated strongly for “constant efforts” by the United States to negotiate a peaceful settlement.

Fourth Annual United States Senate Youth Program, Class of 1966, in the Grand Ballroom of The Mayflower Hotel

Later that week, every delegate had the opportunity to join the staff of one of our state’s U.S. Senators for a day, as well as the staff of our local U.S. Representative. In addition to shadowing Senator Brewster, I also had the chance to follow Representative Charles “Mac” Mathias (R-MD-6th), who at that time represented Maryland’s 6th Congressional District. Two years later, he would run against and defeat Senator Brewster and serve until 1987 in the U.S. Senate. As of today’s date, he was the last Republican ever elected to the U.S. Senate from the state of Maryland.

That says more about Charles Mathias and his particular brand of republicanism than it does about the people of Maryland. Mathias, like many of his Republican colleagues of his generation, supported many ‘liberal’ causes, including civil rights, ending the Vietnam War, and protecting the Chesapeake Bay against environmental damage. And, of course, Democratic Senators and Representatives were also a much more diverse group ideologically.

It is easy to romanticize those times, and certainly within a few short years, the nation would become increasingly torn apart by war, civil disorder and the social and racial stresses that had been brewing for more than a century finally erupting in riots, demonstrations, and assassinations. Perhaps it was nothing more than the naïveté of an 18-year-old, but the Washington that I saw that week exhibited a willingness to put national interest above personal and party agenda in ways that we are unable today.

And, truth be told, we are today a much more honestly diverse nation. Perhaps it is a reflection of my own biases, but during that week, I do not remember hearing from or speaking with a female leader or a leader of color. By my estimation, our delegation was about 65% male and more than 90% white. I suspect that today’s delegations are much more representative of the American people.

At luncheons and dinners, we heard from and got to ask questions of leaders such as Secretary of State Dean Rusk and FBI Director John Edgar Hoover. At one of the dinner meetings, Sargent Shriver, then Director of the newly created Office of Economic Opportunity spoke to us about the war on poverty and his earlier work leading the Peace Corps. As we were all encouraged to do, at the end of his address, I rose to ask a question saying, “Sargent Shriver, would you….” I don’t remember my question. I do remember being gently chided later that evening by our Marine Corps Military Mentor saying to me, “Gary, Sargent is his first name, not his title.” I have never quite recovered from that embarrassment. However, Mr. Shriver didn’t miss a beat and could not have been more gracious, as though it happened all the time, and perhaps it did.

On Friday, at the White House, President Lyndon Johnson greeted us warmly and spoke with us. I remember it mainly as just awe-inspiring to be shaking hands with the President of the United States. The deep polarization that two years later would cause President Johnson not to pursue a second term had not yet begun to strongly develop. I can’t help wondering if the 1968 Senate Youth delegation met with the President, would it be a different kind of meeting?

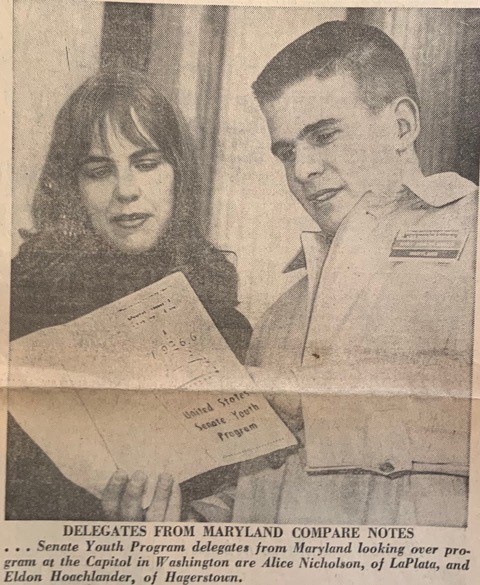

Senate Youth Program Delegates Alice Mae Nicholson (MD-1966) and Gary Hoachlander (MD-1966) review the Washington Week agenda

It has been more than fifty years since the William Randolph Hearst Foundations invited me and 101 other young people to Washington, DC to witness our nation’s leaders, indeed our government, in action. As I’m sure you can tell, it had a profound impact on me and helped shape my future career. I saved newspaper clippings and other mementos of that week, never expecting to share them with others. Rather I kept them just to remind me of the honor I felt to be selected and represent my state.

Of course, the Foundations hosted us, at least in part, because we were all already on a path toward civic leadership and public service. I don’t know how many of my fellow delegates continued on that path, but I suspect an overwhelming majority of them did.

Rarely, if ever, does any single event or experience determine future career or life choices. But there are some that have a major influence, and for me, this was one. Here are a few of my takeaways.

First, to a person, every leader who spoke to us that week deeply valued public service at all levels of government and community action. While there were many policy disagreements between and within the parties, there was nevertheless a strong respect for everyone choosing to work in the nation’s service, whatever form that might take. Stated differently, respecting one another did not depend on agreeing with one another. That’s a quality I fear has largely disappeared from American politics and public discourse.

Second, like so many other aspects of life, government is messy, contentious, and sometimes effective and sometimes not. It serves, as our forefathers imagined, to form a more perfect union, not a perfect one. Achieving that goal depends on all of us respecting our Constitutional foundation, the rule of law, and orderly processes for changing the principles and codes that enable us to function as a democratic society. Allowing that to crumble puts our country, our communities, and our families at unconscionable risk.

Third, for a generation of young people whose slogan would soon become ‘Don’t trust anyone over thirty,’ the adults we met that week displayed great trust in us and a profound hope that we would follow in their footsteps trying to make our communities, our states, our nation, and our world a better place. I hope that we have lived up to those expectations. Nevertheless, there is so much left to do, by us, and the young people who follow. Thank you, Hearst Foundations, for your continued faith in America’s youth.

As we read Mr. Hoachlander’s recollections, fifty years after his Washington Week experience, we are struck by how much has stayed the same and how much has changed in the intervening decades.

A new generation of Hearst family members still personally meet and welcome each year’s delegates. Delegates still have unparalleled access to the nation’s top elected and appointed leaders with vibrant Q&A sessions, even with a few jitters such as occurred in 1966.

Social media and email may have made Arrival Day somewhat different with current delegates knowing their peers before walking into the Grand Ballroom, and post 9/11 security concerns have ended the practice of sending delegates out for solo “shadowing” days on the Hill.

But, the heart of the program, the call to public service, the encouragement of civil discourse, the camaraderie that develops among the delegates, and the return to a hometown filled with inspiration are as true today as then.

Our thanks to Gary Hoachlander for carefully protecting such wonderful mementos from one of the Senate Youth Program’s earliest Washington Weeks.

About the author:

Gary Hoachlander is President and CEO of ConnectED: The National Center for College and Career. Beginning his career in 1966 as a brakeman for the Western Maryland Railroad, he has devoted most of his professional life to helping young people learn by doing—connecting education to the opportunities, challenges, and many different rewards to be found through work.

Widely known for his expertise in career and technical education and many other aspects of elementary, secondary, and post-secondary education, Gary has consulted extensively for the U.S. Department of Education, state departments of education, local school districts, foundations, and a variety of other clients. Gary earned his Bachelor’s degree at Princeton University and holds both a Master’s and Ph.D. degree from the Department of City and Regional Planning, University of California, Berkeley.

Photos provided by Gary Hoachlander